The long-awaited Guild of Book Workers Journal has been published and mailed to members of the Guild. Not a member? Click here to order a copy - - or, better yet, HERE to join, and see what you're missing.

Table of Contents

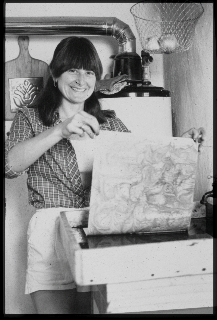

Pamela Smith: The Making of An Edition Paper Marbler

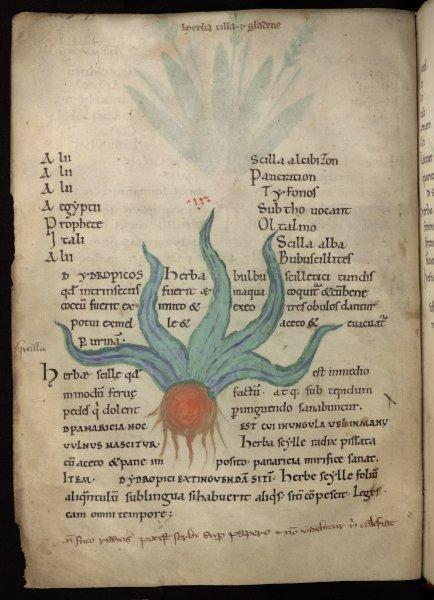

Handmade Korean paper, or hanji, has slowly been gaining attention in the wider art, craft, and conservation worlds. Lee’s studies have led her to an understanding of the methods, history, and uses of this luminous and resilient paper, and a deep appreciation of the contemporary artists who use hanji with innovative, impressive, and always beautiful results. Here she introduces us to the world of hanji and offers a gallery of hanji artists’ work.

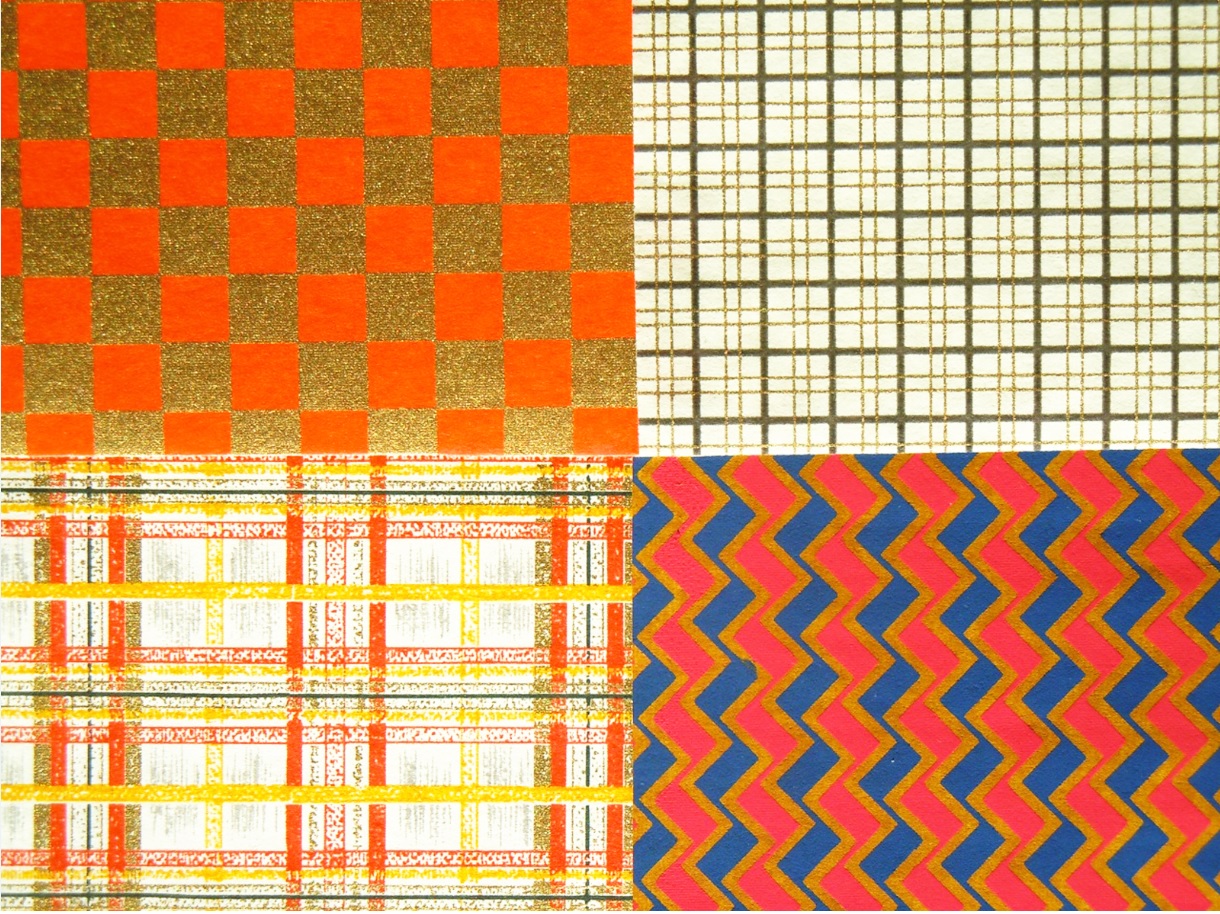

Nancy Jacobi: Chiyogami and Katazome-shi: The Hand-printed Papers of Japan

The current worldwide popularity of the decorative papers of Japan—chiyogami and katazome-shi—would suggest that they are designs hot off the contemporary press. Stripes, dots, checkerboards, multiple lines of geometric shapes, and flowers—these patterns fit perfectly into the current mode for simplicity, repetition, and graphic order. In fact, the origins of the patterns printed today on paper by both silkscreen and stencil often go back 1300 years, following the religious, political, and social history of Japan through its motifs and symbols, and even further back to their roots in China.

Tomaso, a skilled, if fictional, Italian papermaker learned the craft of papermaking as a young person and eventually became well established a paper mill foreman, renowned for his knowledge of the intricacies of the craft. Through his eyes, Barrett gives us a glimpse into what the process of papermaking very likely was in the fifteenth century, and along the way draws attention to those ingredients and processes that result in a truly fine sheet of paper that will stand the test of time.

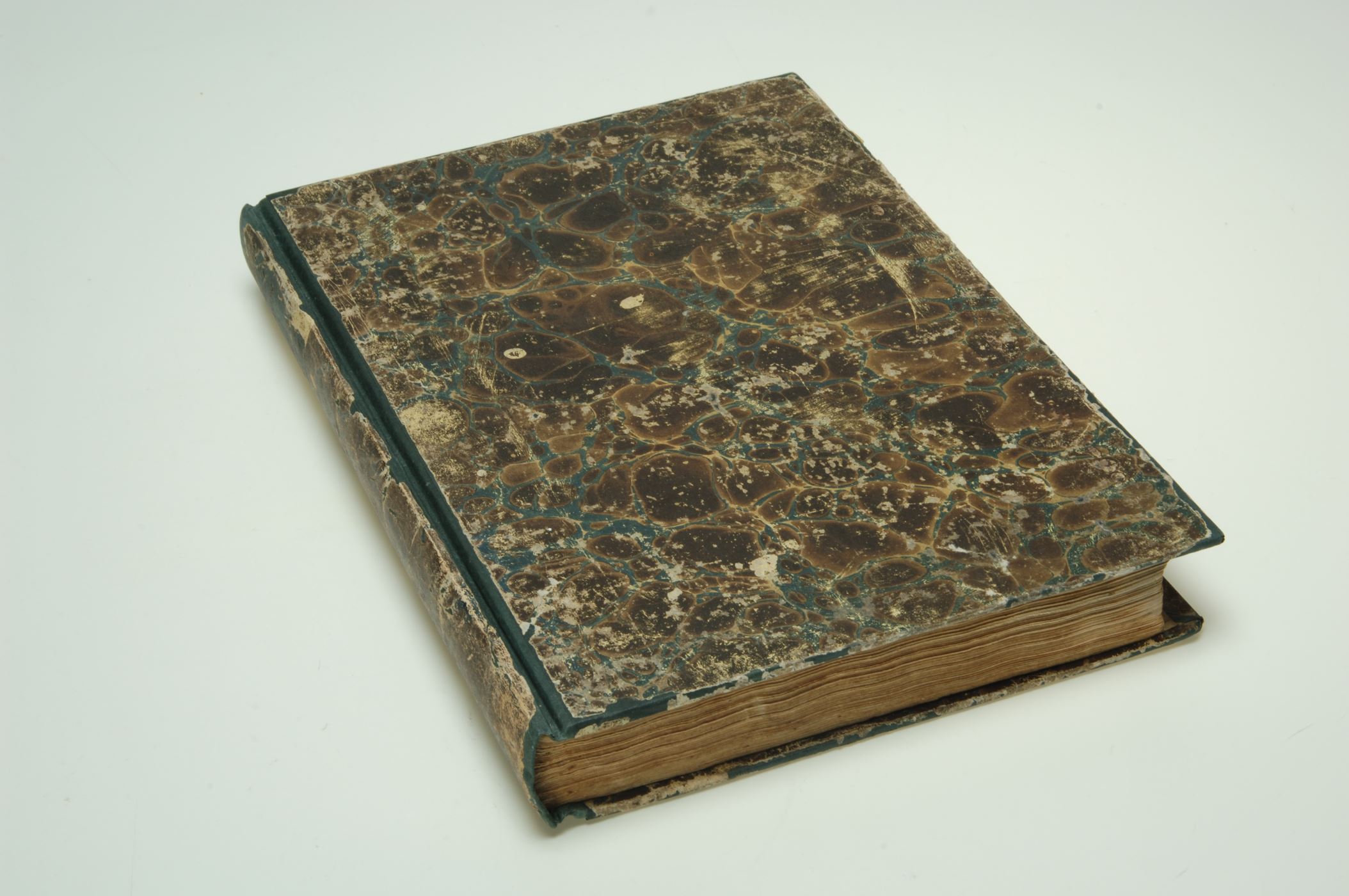

*Katie Smith: An In-boards Paper Binding: P. Cornelii Taciti

Not just for spies and schoolchildren, sympathetic inks—invisible inks—have been around since at least the fifteenth century. Chemically, many sympathetic inks are related to the materials of early photography, document copying, and dyeing, and also to the so-called security or safety inks and papers used to prevent forgery and counterfeiting. In this essay, Rhodes traces the history of invisible inks and discusses the practicalities of using them (such as choice of papers and writing utensils), and the detection of invisible writing.

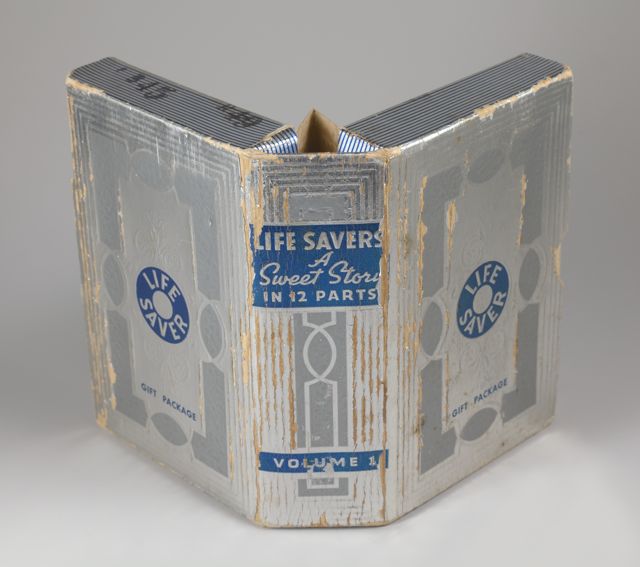

Mindell Dubansky: Blooks: Things that Look Like Books, But Aren’t

Book-shaped objects act very much like true books, in that they are portable objects designed to protect their contentsand also are concerned with the use of beautiful materials and ornaments, as well as the need to educate and amuse the reader for their resemblance to true books and their inventive designs. Dubansky explores the history and structures of these objects, which date from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.