Introduction and Opening Remarks

by Betsy Palmer Eldridge

This article is based on remarks presented at the 2006 Guild of Book Workers Standards of Excellence Seminar, celebrating the Guild's centennial, and is meant to represent the state of the Guild and the book arts at that time.

Betsy Palmer Eldridge joined the Guild of Book Workers in 1960 at the prompting of her mentor, Carolyn Horton, having previously studied bookbinding in both Hamburg and Paris. Forty years later she served as the President of the Guild for six years and chaired its Centennial Celebration in 2006. The story of Rensselaerville and the Huyck paper felt mills came from family members who are Huyck descendants.

A centennial celebration is an impressive accomplishment for a volunteer organization in the arts. To reach it, the Guild has undergone a remarkable metamorphosis over the years. The Guild was founded in New York in 1906 by an enthusiastic and dedicated group of book artisans to “establish and maintain a feeling of kinship and mutual interest,” as stated in the early by-laws. With an early membership of 126, it met informally for support and mutual encouragement, sharing information and planning exhibitions. Forty-two years later, when the membership had waned to only forty-eight members in the wake of World War II, the Guild became affiliated with the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA). This was a much larger organization and was able to provide the Guild with administrative support, plus a place to meet and a small exhibition space.

After thirty years with AIGA, when the membership had revived to over 300, the Guild courageously launched out on its own again in 1978 as an independent not-for-profit organization incorporated in the state of New York. It has since grown to become a national organization with some international members and ten regional Chapters that actively promote the Guild’s aims and purposes on a local level. Currently its membership is just under 1000 members. If there is any truth to the old saying that “the first 99 years are the hardest,” the Guild should have clear sailing ahead!

One thing about a Centennial is that it gives plenty of advance notice. It does, however, still require a great deal of planning. About ten years before the actual anniversary, a number of suggestions were made about how best to celebrate it. New York was the obvious location to many, and fortunately the New York Academy of Medicine, so wonderfully suited to the Guild's purposes, was available. Another idea was that it should be an historical symposium rather than the usual annual Standards seminar format. The consensus was that if the Guild did not stop at this point to try to document the history of craft bookbinding on this continent in the last hundred years, no one ever would.

The Centennial celebration came to pass thanks to the efforts and cooperation of many people. In addition to the organizing committee for New York and officers of the Guild, the hosting institutions in New York and their staff members, the speakers, presenters, exhibiters and vendors contributed enormously to the success of the meeting. The papers presented in the two-day historical symposium documented many significant, but often not well known, aspects of the evolution of the bookbinding craft in America.

The Guild's roots are in the nineteenth century, so a brief look back at that time period is important to set the stage for the centennial papers that follow. Indeed, it was a very different world more than a hundred years ago, a world that is difficult to imagine from the vantage point of the early twenty-first century.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the United States was still a primarily rural, agrarian society, with two thirds of the population engaged in subsistence farming. The Civil War (1861–1865) put the country on the move. Railroads, following the earlier Erie Canal route west, opened up first the mid-west and then the far west. The word “cars” in those days referred to horse-drawn streetcars and the trams and trolleys that crisscrossed the countryside. Automobiles were still in their infancy. The Industrial Revolution was in full swing, with water power running the textile industry in New England. Electricity, which would change so much, was just beginning to light up the night. In 1893 the World Fair in Chicago, the Colombian Exposition, would showcase the new technologies.

In 1906—the year the Guild was founded—a disastrous earthquake destroyed San Francisco, but elsewhere it was a period of great expansion, prosperity, and optimism that fostered the arts. The new urban society had not only a rising middle class but an expanding upper class. Secondary and post-secondary education was more widely obtained, producing a literate and educated population. These people traveled and honed their tastes through exposure to the European arts on the “Grand Tour of Europe.” The pre-income-tax period that ended in 1913 saw not only the massing of major fortunes by the well-known captains of industry—Morgan, Carnegie, Rockefeller and the like—but also the creation of fortunes for many lesser-known families. All along the east coast in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, but also westward in Chicago, Texas, Denver, and the cities of the west coast, a new affluence emerged. In this social and economic climate, the book arts flourished, and it was members of this affluent class who established the Guild of Book Workers.

THE SMALL TOWN OF RENSSELAERVILLE, New York, a short journey up the Hudson River from New York City, was home to a family firm that illustrates the spirit of the period: the Huyck felt mills. Rensselaerville today still looks remarkably similar to this 1860 lithograph of the town. It is nestled in the Helderberg Mountains, north of the Catskills, some thirty miles south of Albany. In the seventeenth century it belonged to the Dutch patroon Van Rensselaer, and in the late eighteenth century it was settled by Revolutionary War veterans from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and eastern Long Island, attracted by its native forests (for lumber) and its streams (for power). During the nineteenth century it was the home of the prosperous Huyck family, whose woolen mills made felts for the burgeoning American paper industry, which makes it especially interesting to us.

A small stream, Ten Mile Creek, flows out of Lake Myosotis and drops down over the 100-foot Rensselaerville Falls into a deep gorge. At the bottom of the falls are the clapboard mill house and the picturesque Lincoln mill pond, where water for the mills was stored. Below the pond is the one remaining mill. Once there were twenty-seven mills in this area: lumber, grist and woolen mills, plus a hemlock leather tannery. The Huyck woolen mill was one of the first American mills to manufacture papermaker's felts. The American paper industry had grown exponentially after the Revolutionary War, and subsequent tariffs had curtailed imports from abroad. Paper was in demand, and so was the felt to make it. Today the mill is the home of the Town of Rensselaerville Historical Society, and it serves as the headquarters for the Edmund Niles Huyck Nature Preserve.

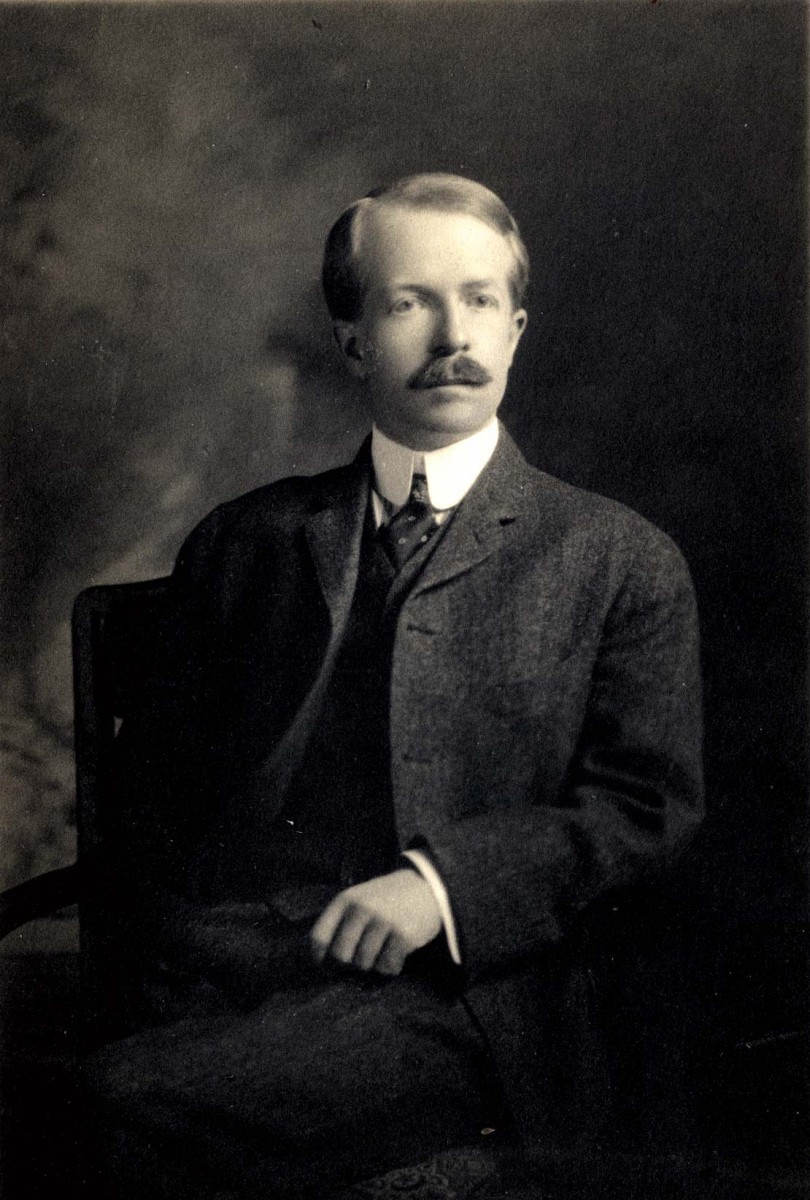

Edmund Niles Huyck was born in 1866, the third generation of the Huyck family in Rensselearville. An astute businessman and enlightened employer, he ran the family’s papermaking felt business with his two brothers. In 1891 he married Jessie Van Antwerp from Albany, also of Dutch descent. Although her father did not believe in formal higher education for her and her six sisters, she had a keen mind and was extremely well read.

In 1898 Jessie and Edmund had a summer home built in Rensselearville, while they lived in Albany during the winter months. Nature-loving and public-spirited philanthropists, they later entrusted the family’s lands in Rensselaerville to found the two-thousand-acre Huyck Preserve as a bird and wildlife sanctuary. Their house is now part of the Rensselearville Institute and Conference Center.

Jessie later became active in a number of organizations—The League of Women Voters, the Foreign Policy Association, the World Affairs Council—and personally knew Eleanor Roosevelt, Governor Averill Harriman, and Madame Chiang Kai-Shek. For those who were literate and cultured, books—and having a library—were so very important then. No wonder that Morgan collected books and that Carnegie built libraries. No wonder that the Guild was founded in 1906. All of it came out of that same spirit in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: a love of books and a fascination with everything about them.

Eventually the mills moved away, over to Kenwood near Albany, to be closer to rail and water transportation on the Hudson River. However the town of Rensselaerville, so lovingly cared for by the descendents of the original families and now on the National and State Registers of Historic Places, retains its charming nineteenth-century character.

The creek ran the mills, the mills made the felt, the felt made the paper, the paper made the books, and then the books were bound. The story of Rensselearville and the Huyck felt mills is only one small part of the much larger picture of books in this period in America. The Guild of Book Workers would play its own special part in that picture as it emerged, as was told in the various Centennial presentations that are published in this special issue of the Guild of Book Workers Journal.