Teaching the Book Arts

by Hedi Kyle

This article is based on remarks presented at the 2006 Guild of Book Workers Standards of Excellence Seminar, celebrating the Guild's centennial, and is meant to represent the state of the Guild and the book arts at that time.

In 1959 Hedi Kyle graduated from the Werk-Kunst-Schule in Wiesbaden, Germany, with a degree in graphic design. Shortly afterwards she immigrated to the United States. In the early seventies she embarked on a career as book conservator. At the same time she became aware of artists’ books and began to experiment with untraditional structures. She contributed to the growing interest in the field of book arts by teaching workshops for more than thirty years. Her one-of-a-kind book constructions were purchased by numerous institutions and individuals. She has had several one-person exhibitions and shows her work as part of diverse groups of book artists here and abroad. In 2003 she retired as book conservator of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. Until May 2013 she held her position as adjunct professor at the University of the Arts where she instructed students in the MFA Book Arts and Printmaking program. In November 2013, she and her husband moved into a renovated cottage in the Catskill mountains where they live year-round. Hedi Kyle is an honorary member of the Guild of Book Workers and a co-founder of Paper & Book Intensive (PBI).

We all love books. We have made books with our own hands and we look at books with a knowing eye, identifying the style of binding, evaluating design and craftsmanship. We are here today celebrating one hundred years of nurturing the handmade book.

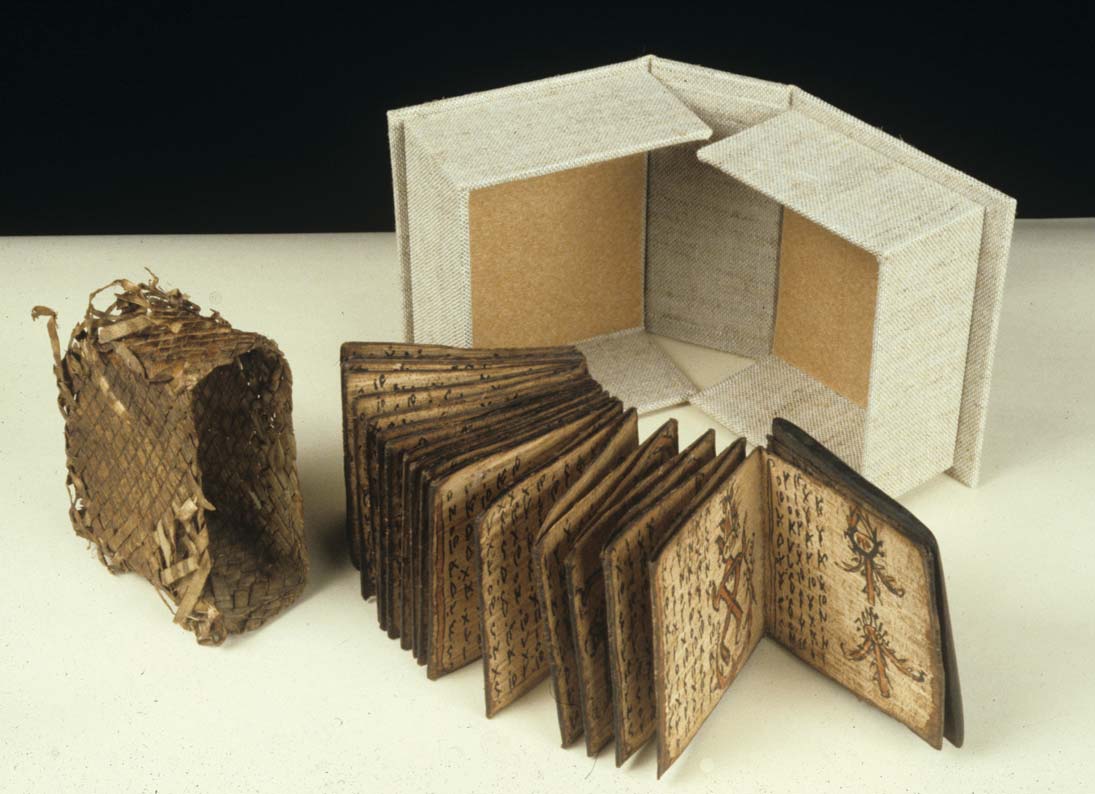

Let us for a moment recall how countless artists throughout the ages have described the book through visual means and left a record of its social interaction and its physical features. Seemingly outdated and no longer part of the mainstream of book production, these images today ignite a spark and awaken our interest to investigate the book in a new way. Libraries hoard a wealth of binding styles. Exploring their collections and bringing to light almost forgotten treasures is part of the Guild’s achievement over the past decades. Ancient binding methods are revived and modified, old materials are researched and new ones created. Aesthetics matter; so do durability and sound technique. Standards of excellence become a goal. As electronic media threaten the book’s decline, it gains momentum instead and moves in a new direction.

During the 1960s and ‘70s an evocative transformation took place: Artists discovered the book as an open-ended vehicle to transport content hitherto rarely encountered in the book format. The traditional structure itself was also challenged by work extending into the realms of architecture and sculpture. To many members of the Guild this was not readily acceptable, and when a new establishment called the Center for Book Arts (CBA) was founded by Richard Minsky in New York City in 1974, it caused quite a swell of resistance. Book exhibits at the time still featured mostly traditional work. And yet against all odds, those books ended up standing next to contemporary innovations, so-called “artists’ books.”

Ornate leather bindings were long the center of attention. Therefore, the first step toward acknowledging new directions was taken with caution until, slowly but surely, the horizon widened. The old and the new could coexist after all. It is no longer a blasphemy to call examples as you see in these slides “books.” Neither is it a travesty that one could learn to make such a thing without serving a lengthy apprenticeship. Being able to create a book with simple means and limited experience is not a bad thing in a time when we are yearning to get away from the computer flatland. What is objectionable, however, is to assume that this is all there is to making books and begin to teach this kind of thing with an aura of authority.

The Center for Book Arts had just such a reputation at first, but nobody holding that opinion actually looked closely at the Center’s activity. In fact, tradition and craftsmanship were not at all shunned, either in the early years or now. Instead, the old and new inform each other and there is emphasis on learning, research and experimentation. Ironically, in those first years the Guild and the CBA often invited the same instructors to teach workshops, and some participants were members of both organizations. Today the CBA is considered a pioneer in the field and a forerunner for other book art centers, which follow the same basic structure: promoting workshops and ongoing classes in bookbinding, letterpress and papermaking. Beyond hands-on participation, exhibitions and lectures at these centers draw in people from the community at large.

The one thing book arts centers do not offer are formal degrees. Growing interest in the book arts and related fields has increased the need for study opportunities in greater depth, leading to BFA and eventually MFA degrees. All over the country, courses are now offered at universities, colleges, art- and library schools. MFA programs have existed for over twenty years at such locations as the University of Alabama in Tuscalusa, Columbia College Chicago, Purchase College—SUNY, and the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. It is worthwhile to thoroughly research each program, become familiar with the facilities they have to offer, and last but not least consider the infrastructure of the community and city in which they are located.

All programs draw from the prolific field of book arts. Some focus more on fine press books, while others encourage book works that challenge conventional format and content. Craftsmanship and technical skills are emphasized in master bookbinding, papermaking, and printing. Students also have a chance to work in state-of-the-arts computer labs. A roster of internationally known book artists, printers, writers, papermakers, and critics make their rounds as they are invited by each institution to lecture, teach and show or read their work. This offers students opportunities to observe and sometimes assist distinguished practitioners in the field. The connections made under those circumstances are valuable assets and often help when seeking future employment. All in all, four semesters will prepare the student for a professional career in the field.

The program I know best is the Book Arts and Printmaking Graduate Program at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. It was inaugurated in 1989 by Ed Colker, the provost at the time, and since that time I have instructed students in bookbinding techniques. My course is offered every semester and it is mandatory. Other studio requirements include Concept, Image, Type, and Color Mark. Several colloquia address the Artist’s Book, the History of the Book, Art and Design in Society, Structure and Metaphor, as well as Professional Practices. Students also have a choice of electives. Access to metal, ceramic, fiber and wood studios is an important issue and has led to multimedia installations.

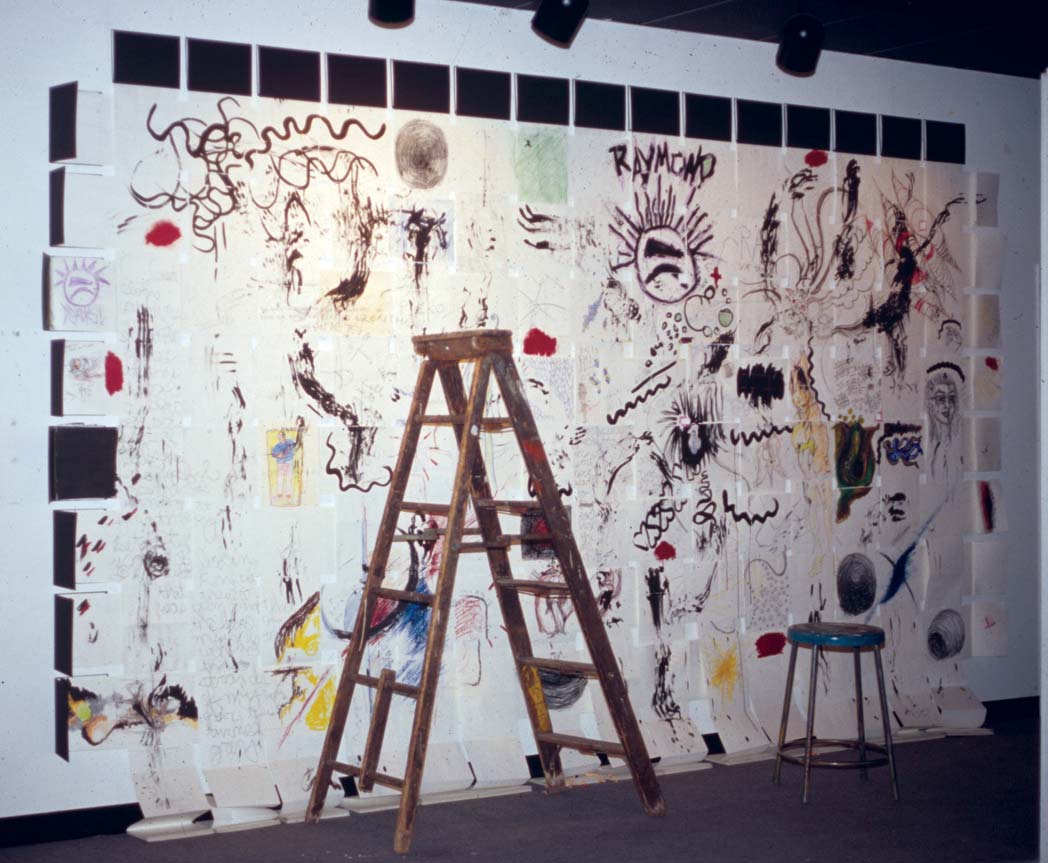

The four-semester, 60-credit course of study culminates in a thesis exhibition. The exhibition takes place either in one of the University of the Arts galleries or, as has often happened in the past, at a space in Old City, Philadelphia’s gallery district. In either case, the opening date coincides with First Friday, when a maximum number of viewers can be expected to visit the shows. The gallery space is determined ahead of time so that students are able to develop their concept with their individual space in mind. The MFA candidates rarely show books alone. More often we are surprised by installations with the book as focus point. Visitors, however, will not miss out on an intimate encounter with books. A designated reading area displays all the books students have produced during the four semesters and invites viewers to browse, read, and touch. Twice a year, in the spring and fall, a book party takes place. Great posters are designed and letterpress printed to announce this event. The public is invited. All books may be touched and read. Many of them are for sale, as is other printed matter such as broadsides and cards. The high point is the arrival of the librarian, who will choose work for the artists’ books collection, which is continuously growing and well worth a visit. There are other venues where students may sell their books, such as conferences and fairs across the country, Oak Knoll Fest, and the holiday fair at the Center for Book Arts in New York City.

Assistantships in the program itself are available during the course of the four semesters. These assistantships often become stepping-stones for later teaching appointments within the university. Students also have an opportunity to intern in galleries, the Print Center, the Fabric Workshop, and several conservation labs, including the Library Company, the Philadelphia Historical Society and Free Library, the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts, and the American Philosophical Society. These internships have proven to be of great advantage, especially those in conservation. At the American Philosophical Society, where I was head conservator for seventeen years until my retirement in 2003, I was able to train two or three students every year, thanks to the generous support of the librarian, Dr. Edward Carter. Fortunately Denise Carbone, a 1991 graduate of the Book Arts and Printmaking Program herself and now my successor, is able to continue offering the internships, which are in high demand, for good reason. Working with real materials in a research library setting introduces the interns to a full spectrum of conservation options and treatments. They are also stimulated by the nature of the materials with an affinity at times to contemporary book works. The technical skills required to do the work are closely related to what they already practice in producing their own work. One compliments the other, and it has become very obvious that a substantial number of graduates over the years found employment in conservation.

Other internships as well have proven to be career pointers. Quite a number of the alumni who originally came from other parts of the country to join the program are now working here in Philadelphia in their field, and they have decided to stay. It does not always happen right away, and some graduates have to take less distinguished jobs at first to pay their bills. Yet as far as I keep track, sooner or later most of them are able to find meaningful positions. Less than forty years ago nobody belonging to the Guild of Book Workers then could have predicted such a surge in the field. Hand bookbinding was just about the most obscure craft and most people had no idea it still existed. So let us celebrate today. We all have contributed to the revival and rediscovery of the book.

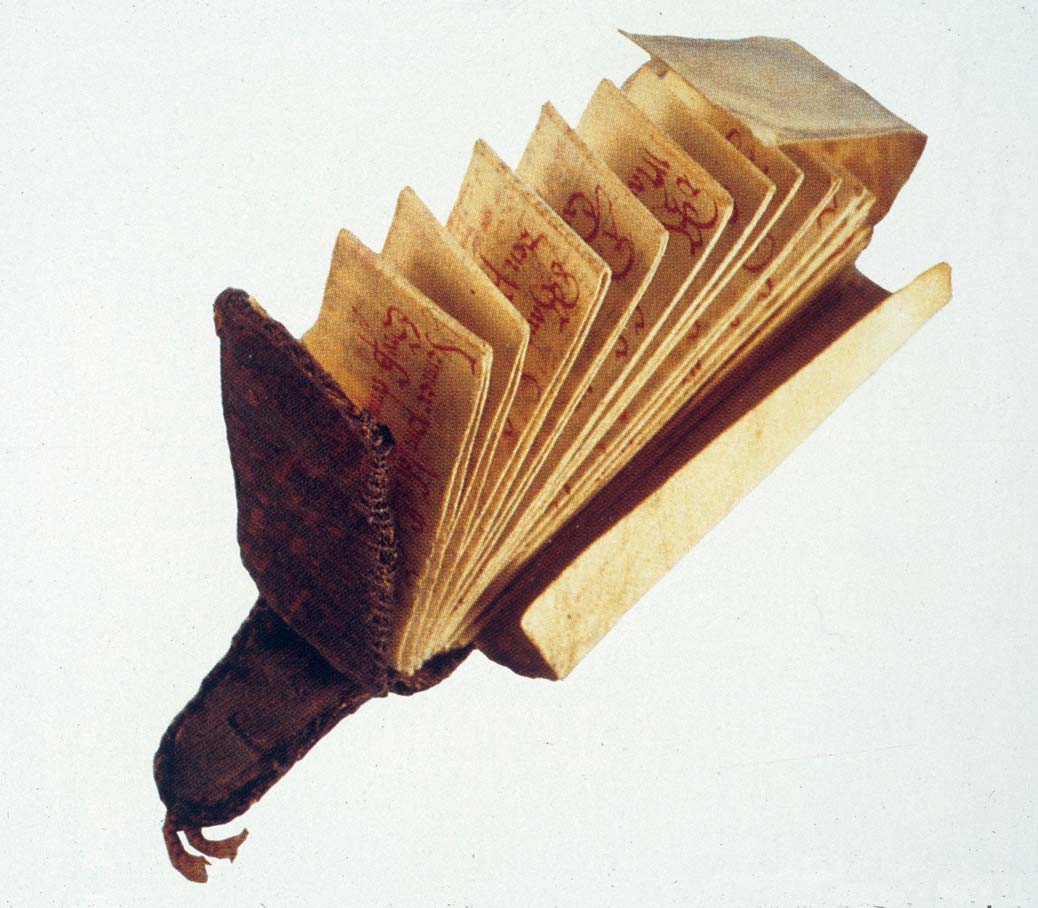

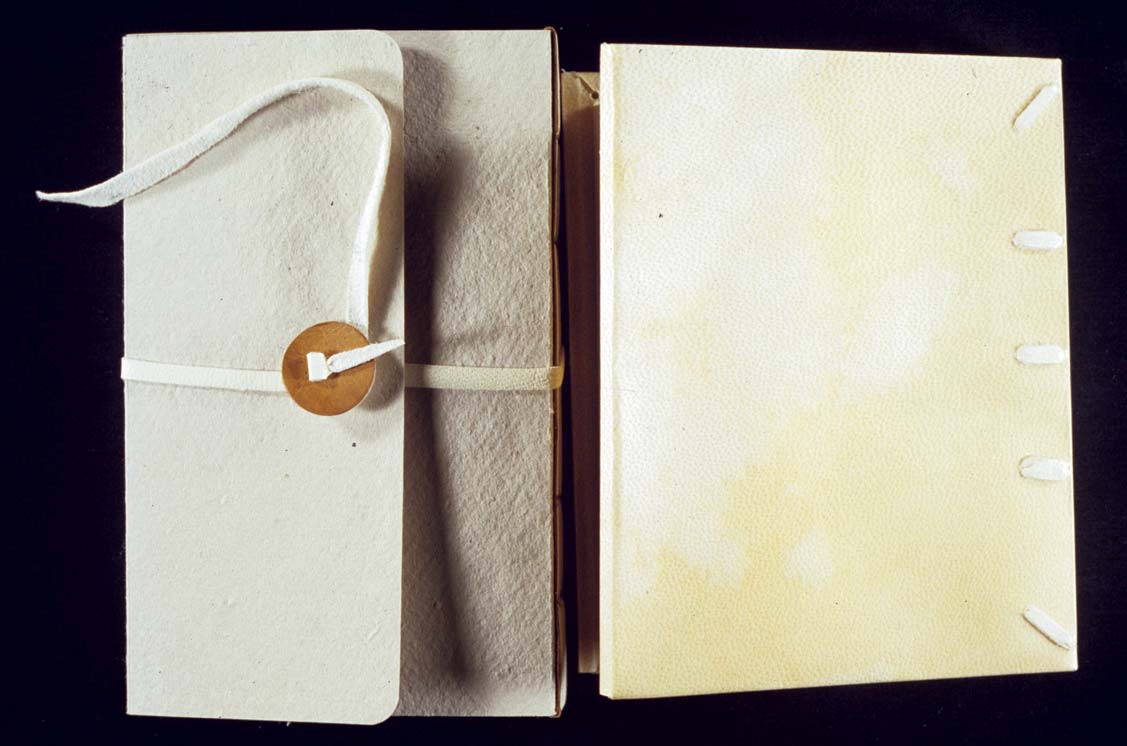

The images that follow are a selection from more than 100 slides that illustrated my talk at the Guild of Book Workers centennial celebration. They represent historical and ethnic book forms as inspirational points of departure (figs. 1,5, and 6); work by student conservation interns, many of whom later found employment in the field (figs. 2 and 7); and innovative work by students and influential teachers (figs. 3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12).

Fig 1. Vade Mecum, Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, Germany. Medieval reference book format with great potential for book artists.

Fig 10. Models for conservation bindings based on historical flexible paper and vellum covers. Made by student conservation intern at the American Philosophical Society.

Fig 11. Mi-Kyoung Lee, MFA Book Arts and Printmaking Program, University of the Arts, Philadelphia. Installation of blank concertina books inviting viewers participation