Which would you say are the projects/bindings that have intrigued you the most and why? This applies to commissions you’ve received but can also be extended to the work of other fellow binders that caught your interest.

I’ll share two of my favorite commissioned pieces and a quick binding that I did on the side:

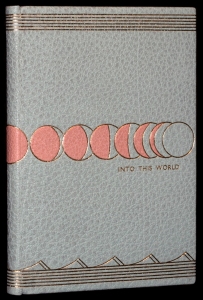

Into This World, a poem by Natalie Goldberg, illustrated by Clare Dunne and printed by Sialia Rieke, is a binding that was able to be somewhat emotional. I wanted to capture the femininity of the poem & illustrations in the design, as well as the strength of spirit necessary it takes to become one with the world, dying with grace: “let us die/ gracefully/ into this world”. I also wanted to convey the sovereignty of nature over our lives, and that it will be here when we are gone, beautiful as ever. The waxing and waning moon is at once an expression of nature itself interacting (drawing the waves up) within the world, a physical representation of the constant change in the world, as well as a metaphor for the progression of the human life. It is also meant to strike a chord with the overall tone of femininity. The death explored in this poem is not about the pain that often comes before death, but rather a celebration of the transformation of the body and the spirit in its continuation of being a part of this world, in a different form: “…let us […] not hold on/not even to the/ moon/ tipped as it will/ be tonight/ and beckoning/ wildly in the sea”.

My binding on Paul Needham’s “Twelve Centuries of Bookbindings” was a fun and somewhat technical binding because it allowed me to make a statement about the history of bookbinding. Often the history of bookbinding is more correctly the history of book decoration and -even more correctly- it is most often the history of gold-tooled bookbindings. The time period covered in those twelve centuries was 400-1600, so there’s not too much time in there for gold tooled bindings, however, they constituted more plates than blind tooled bindings. So with the binding I let the gold do what it normally does—draw attention away from blind tooling in a very stark way.

I don’t really have any opportunity to address politics in my work. With the kind of work that I do, it just doesn’t come up. And with the political realm being as divisive as it is, I imagine it could put people off. I’ll do my best to make this paragraph as non-controversial as I can. I chose to do a binding on a book written by Bernie Sanders. He’s not a new politician, and none of the policies that he supports and is pushing for are new ideas. This book follows his campaign trail and puts forth the ideals he ran on: income equality, health care for all, higher education as a human right, racial justice, environmental justice, criminal justice reform, immigration reform, getting money out of politics, truth, love, compassion, and solidarity, among many others–and their implementation. All of these are pressing issues in society and need to be addressed in a moral manner, not limiting the rights of people to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness (the stated goal of the country I live in).

I chose to do a utilitarian binding on this: no gold, nothing flashy, a simple arts-and-crafts design tooled in blind, with an off-cut piece of leather, done quickly but with elegance. The endpapers are plain, they don’t need to be fancy. “A Future to Believe In” was Bernie’s campaign message, and “The Struggle Continues” is the progressive answer to any election, any vote, or any compromise, win or lose–the struggle continues.

There are a number of bookbinders, current and past, who I look up to, but none moreso than the Spanish bookbinder Emilio Brugalla. His work ranges from historical to contemporary, always tooled magnificently and the ability to work in any style fairly seamlessly reflects what I attempt to do in my work. He said, “El corazón del libro nunca deja de latir.” I’m not a spiritual person by any stretch of the imagination, but there is something living and beautiful within a book that the right binding can be resonate with that causes an intangible sense of wonder, and truly the heart of the book never stops beating.

Your bindings are excellently tooled, a fact I’ve seen mentioned within the bookbinding community. You also offer finishing services and teach courses on tooling and gold-finishing. Given your focus on the specific aspect of the craft, what would you consider the hardest part in mastering tooling and why?

The only claim I make is that I am a competent finisher. Because I am not a master, my speculation is that the hardest part in mastering finishing is achieving a level of mastery with all styles of finishing and sustain that for quite some time. This also includes 1. Having the range of tools and type needed for this, and, more difficult, 2. Having the work coming through your shop to sustain your finishing practice week by week. Since I spend a decent amount of time forwarding, that’s time away from the finishing stove, and teaching, while still finishing, is more instruction than actual finishing. I hope one day to become a master, but it’ll take a lot more time.

For those starting out, finishing is not an easily won skill. It is among the most difficult aspects of creating a fine binding. Instruction is one aspect of learning finishing, the other is understanding how each impression needs to feel to be successful — that second part I am either not skilled enough with words to describe, or it is a conversation that needs to happen between the leather and the tool in your hand, incapable of being expressed by words. You will make mistakes. You will “waste” gold, or, more correctly, it will take more gold than you feel comfortable using to develop your hand skills. You will likely ruin a binding or two so that you have to re-do it, even if you have been fastidiously practicing on plaquettes. These are all part of the learning process and should not be interpreted as failures, but as necessary steps to being able to tool a binding well.

Is there a specific philosophy behind the way you run your bookbinding classes? How do you approach tool-finishing as a teaching subject?

I take a very systematic approach to teaching finishing. Make sure that you align yourself squarely to the edge of your bench. Make sure you tool your lines perpendicular to your bench’s edge, and rotate the book you are tooling on rather than pivoting your body. Heat the tool, cool it, polish it, tool. These are a few of the things that I repeat over and over during the course of my workshops. My intro classes start with straight lines. I’ll demonstrate the process, have the students try their hand at is, and then demonstrate again, have the students practice, and demonstrate again so that the students can see the process again and focus on a new aspect of the process or notice something that they were doing wrong. It’s rigorous and intense.

The workshops that I teach are often five-day workshops, though I’ll teach two-day workshops as well. We use high quality materials, as these give the best results with unpracticed hands, and it’s easier to know what the issues are when the materials are reliable. Within every class there is a range of previous finishing experience, and not everyone learns at the same rate, so I address this by giving each student as much one-on-one time as I can. This allows those with more experience to move forward and be challenged and those with no experience learn enough to go off on their own. As I mention above, finishing is among the most difficult aspects of fine bookbinding and, for me, the more people that are doing it, and doing it well, the better.

I’m in the process of making the first of what I hope will be a number of instructional videos on finishing, since access to that kind of information is somewhat limited. The first will be the core of what my five-day class is, blind tooling and gold tooling with synthetic glaire and gold leaf. If that goes well, I will move on to cover some of the other aspects of finishing that could benefit from instruction: titling, tooling with egg-glaire, tooled-edge onlays, to name a few.

As artisans we have to deal with misconceptions about our craft on a regular basis. People for example are often used to seeing intricate decorations on bindings, most notably in films and series, which makes it difficult to explain the level of skill and experience required to produce such a result.

What can you tell us on the subject of misinformation regarding bookbinding? How -if at all- has it affected you so far and what can a craftsman do to tackle it effectively?

As bookbinders, one of our most important roles is to teach others about bookbinding, whether they be clients, prospective clients, someone you happen to bump into and start a conversation with. In the past, one way to address this was to print out a list of each and every step to let people know what the steps were and how many of them there are (I’m referring to the “The bookbinders case unfolded” broadside that lists all of the steps in bookbinding, dated between 1669 and 1695). I’ve had instances where the desired date of completion was ten days or so, and that answer is always, “It would be especially rare that you would find any hand bookbinder with that short of a promised turn around. Most binders you will find will have projects they are already working on, and a more realistic baseline for turnaround starts around six weeks to three months.” Now, that’s not true across the board, depending on work flow, the speed that a binder works at, or if it’s a job you can slip in between other jobs. It’s always best to over budget time and get a binding to someone earlier than you estimated than to miss a deadline.

People will always have misconceptions about things they’re ignorant of, just like in every other facet of life. If they simply do not know that a fine binding will take a few months at the earliest, it is good to let them know how long a binding takes, keeping in mind the projects that need to be completed before starting a new one. There’s no positive result from being elitist, condescending, or dismissive, regardless of how much time goes into building up our hand skills. An authentic and genuine conversation, along with showing examples of work, goes a long way.

Last but not least: can you share a small piece of bookbinding wisdom that you’ve unlocked through personal experience?

The bit of wisdom I’ll share here is a branch off of something that I heard often as a student: do the kind of work that you want to do. If you take in a bible repair project, then people will know you do that as part of your work. This applies to everything: repair, restoration, conservation, editions, fine bindings, design bindings, and so on. What I have learned is this: If someone doesn’t know that you exist, they cannot commission a binding from you. It’s a simple enough thought, but for me it has been the thing that keeps work coming to my bench. As a previously very shy person, it was a small hurdle to overcome, but it’s part of the process of being a bookbinder. Put in the hours you need to produce salable work and then make sure the people who seek out that work know you and your work.

koutsipetsidis.wordpress.com/2017/09/25/techniton-politeia-interview-with-samuel-feinstein-part-2/